Join our mailing list for the latest news on Mobituaries, plus receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

By clicking “Sign Up” I acknowledge that I have read and agreed to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Join our mailing list for the latest news on Mobituaries, plus receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

By clicking “Sign Up” I acknowledge that I have read and agreed to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Between late 1962 and late 1963, an American comedian found himself in a brief and rapturous period of astounding fame. Across the country, thousands tuned into their radio and television sets to hear his iconic impersonation, and roared with laughter when they played his hit album.

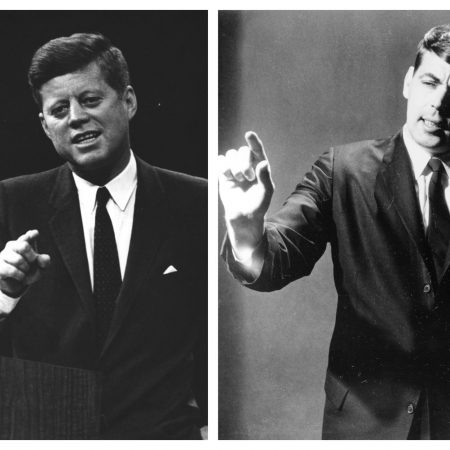

The man was Vaughn Meader, and the act was his shockingly spot-on impersonation of John F. Kennedy. Meader’s album,“The First Family”, which featured his impersonation of JFK, became the fastest selling album up to that point in the history of the record business.

Today, few recall the name Vaughn Meader.

For other entertainers who faded from the spotlight, it may be difficult to trace to the precise moment their popularity declined. But for Vaughn Meader, the end of his career came upon a day that most everyone remembers with chilling accuracy, a day that is still today regarded as an eternal dark mark on America’s history.

Three shots rang out in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963, and America as it was known was forever changed. As a country went into shock and entered a period of mourning, Vaughn Meader slipped quietly away from the spotlight.

Abbott Vaughn Meader was born in 1936 in Waterville, Maine. After his father drowned, Meader’s mother moved from Maine to Boston to work as a cocktail waitress. The young Meader shuffled between the two states often, spending much of his time in a children’s home. Meader says his talent for comedy first blossomed when he was young—he would make jokes to charm his way out of a punishment.

As Meader approached adulthood, his mother was institutionalized and he ran away to join the army. While he was stationed in Germany, he played in a band and met the first of his four wives. After his service, Meader returned to New York City, first doing a risqué piano act and then a politically-themed comedy routine in Greenwich Village. It was during this time when he dropped his first name, Abbott, and became Vaughn Meader.

When Meader performed his political routine on the show “Talent Scouts,” he caught his big break. It was two particular viewers who would change the course of his life. In the early 1960s, aspiring record producers Bob Booker and Earle Doud came up with an idea to capitalize on the nation’s fascination with the new president as well as the popularity of comedy albums. They would satirize the president and his family by placing them in every day, even mundane situations like a White House press conference where the president addresses household toy distribution.

Booker and Doud knew their unique concept would be a hit; they just needed to find the right voice. On July 3rd, 1962 when they tuned into “Talent Scouts,” the pair knew instantly they had found their man.

Remarkably, at the end of that career-making appearance on “Talent Scouts,” Meader made a disclaimer to the audience. He looked at the camera, saying, “I’d like to make one final statement at this time. And I would like to make that final statement as myself, Vaughn Meader. And that is to say, thank you to the United States, a country where it is possible for a young comedian like myself, to come out on television before millions of people and kid its leading citizen. Thank You. Good night.”

After discovering Meader on “Talent Scouts”, Booker and Doud had their Kennedy but top record labels kept turning them down fearing that lampooning the president might prove too controversial. (The labels’ fears weren’t entirely unfounded. One of Kennedy’s closest advisors, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., mistook “The First Family” album playing on the radio as the actual voice of Kennedy. He drafted a memorandum to the President, saying it raised concerns over what a President should do about mimicry.) Finally, on the advice of a network executive, the partners approached a smaller label called Cadence that picked it up instantly.

The producers and "First Family" cast recorded the album in front of a live audience. Afterwards, Booker handed the album to a DJ friend at WINS radio in New York. The friend thought it was sensational and played it on air for three hours straight. That was it. With lightning speed, an unknown comic was launched into stardom.

Suddenly, everyone wanted Meader to appear on their television or radio show. “The First Family” became the fastest-selling album of its time. Vaughn Meader won a Grammy for Best Comedy Performance, and “The First Family” won Album of the Year, beating out the likes of Tony Bennett and Ray Charles.

From the beginning of his meteoric ascent to fame, Meader wanted to do more than impersonate Kennedy. He had dreams of acting in other productions, doing different comedy routines, even singing and playing the piano. But there was only one act the public wanted to see; only one voice anyone wanted to hear Meader impersonate. Meader was under contract to do a “Volume Two,” but he was so reluctant to record another “First Family” album that Booker had to initiate a million dollar lawsuit before he begrudgingly agreed. “Volume Two” was released in the spring of 1963. It sold well, but nowhere near the original album. It would be a short few months later when, in a dark twist of fate, Meader saw his dreams of a life beyond Kennedy fully realized. Meader was in Wisconsin for a show, riding in a taxi, when he heard the news that shook the world: President Kennedy had been assassinated. Meader says he went to his hotel, got drunk, and “stayed drunk.” It was the start of a substance abuse problem that would span the rest of his life. Meanwhile, Booker pulled both “First Family” albums from stores.

Meader immediately stopped appearing in public as JFK and wrote a condolence letter to First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. This sensitivity to the Kennedy family was not out of character for Meader. Throughout his short career as a JFK impersonator, he expressed the hope that his work didn’t displease the Kennedys. On the night of “Talent Scouts” before he was contacted by his future album producers, Meader wrote a letter to JFK himself, part of it reading, “I impersonated you but I did it with great affection and respect. Hope it meets your approval.” The "First Family" record did reach Kennedy, and it was reported that the President enjoyed the album and even gave out copies for Christmas. When asked about it at a press conference, he joked, “I thought it sounded more like Teddy than it did me…” The condolence letter to Mrs. Kennedy, though, may not have been as well received. She supposedly hated the album, saying in an interview she didn’t like how it made fun of her children.

In the subsequent years, Meader released comedy albums in his own voice. They received nice reviews but didn’t sell. Soon, he largely disappeared from the public light.

Nearly forty years later, at 62 years old, Meader sat down for a TV interview. It was for a “where are they now” segment on a short-lived CBS cable channel, “Eye on People”. In the footage, Vaughn Meader appears haggard, older than his years.

Then, he does something unexpected and extraordinary. The interviewer makes a special request, and after some tortured reflection, Meader resurrects his Kennedy impersonation, saying in the voice of Kennedy: “Two hundred years ago in Concord Massachusetts, a shot was fired that was heard around the world. The first bullet, fired from the Concord Bridge, signaled the birth of the American spirit. The second bullet, fired from the Texas Book Repository, attempted to end that spirit. And we’ve seen in the last thirty-something years, how nearly successful that second bullet was. But in the final analysis, there is no bullet, there is no bomb. There is no power on the face of this earth that can destroy the American spirit.” Meader in his own voice finishes with, “Maybe he’d say something like that. I don’t know.”

The Vaughn Meader interview from 1998 was one of his final television appearances. He died six years later on October 29, 2004.