Join our mailing list for the latest news on Mobituaries, plus receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

By clicking “Sign Up” I acknowledge that I have read and agreed to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Join our mailing list for the latest news on Mobituaries, plus receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

By clicking “Sign Up” I acknowledge that I have read and agreed to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

On May 13, 1862, just over a year into the Civil War, an enslaved man named Robert Smalls, who labored on a Confederate steamer in South Carolina's Charleston harbor, set into motion a daring plan.

As his great-great-grandson Michael Boulware Moore explained, "He saw that the Confederate crew had left, and he knew that oftentimes they left for the evening, not to come back until the next day."

For Smalls and six other slaves and their families, the stakes couldn't have been higher. "They knew that if they got caught, that they would be, not just killed, but probably tortured in a particularly egregious and public manner," said Moore.

Disguising himself in the straw hat and long overcoat of the ship’s white captain, Smalls piloted the ship past Fort Sumter towards the Union blockade, and freedom.

"It really blew people's minds because, you know, it just was beyond what people thought an enslaved person could do," Moore said.

After serving on a Union Naval vessel during the Civil War, Smalls returned home to Beaufort, S.C., and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives – one of more than a dozen African Americans to serve in Congress during the period known as Reconstruction, when the formerly-rebel states were reabsorbed into the Union, and four million newly-freed African Americans were made citizens.

"It was a time of unparalleled hope," said Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, who latest book “Dark Sky Rising” is about Reconstruction.

Gates said Reconstruction is one of the most misunderstood chapters in American history, when black men could vote, and would be elected to represent Southerners in Congress.

Rocca said, "You go and you ask people on the street who the first black person was elected to the U.S. Congress, they're gonna guess it's the 1960s, the 1970s."

"And they would never guess it was Hiram Revels from Mississippi," said Gates.

Hiram Rhodes Revels was born free and served as a chaplain to black regiments during the Civil War. On February 25, 1870 he was sworn in as a Senator from Mississippi, an office once held by Jefferson Davis, who left the U.S. Senate to become president of the Confederate States of America.

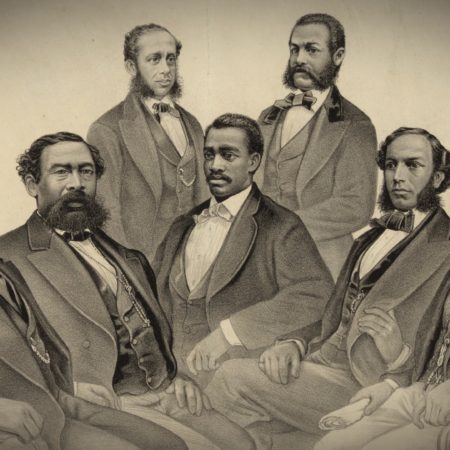

It was an historic moment, said Gates. "And it's memorialized in the famous Currier and Ives lithograph that shows the first senator and members of the House of Representatives who were African Americans.

The famed printing house created the lithograph featuring the African American Members of Congress - all of them Southerners, all of them Republicans - in 1872. Harvard University's Houghton Library houses one of the few known copies.

"When Frederick Douglass saw the portrait of Hiram Revels, he said, 'At last, the black man is represented as something other than a monkey,'" said Gates.

And of the seven men pictured, only two had been born free men; the others had been other people's slaves.

Columbia University historian Eric Foner said, "It's the first time in this country, or really anywhere, that an interracial democracy was created."

He estimates that about two thousand African Americans held some kind of public office during Reconstruction. "We tend to think of slaves as ignorant or unsophisticated. But you know, they had been living in American society for their whole lives, and their parents had, too. The slave trade from Africa had ended long before. These people were Americans. And they wanted the same rights, the same opportunities as free white people had."

In 1874, the U.S. Congress debated a civil rights law that would outlaw discrimination based on race in hotels, theaters, and railway cars. The highlight of debate came when South Carolina Congressman Robert Brown Elliot faced down the bill’s chief opponent Georgia Congressman Alexander Stephens. Just thirteen years earlier Stephens, then Vice President of the Confederate States of America, had given a speech proclaiming slavery was the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy.

“The progress of events has swept away that pseudo-government which rested on greed, pride, and tyranny; and the race whom he then ruthlessly spurned and trampled on are here to meet him in debate,” Elliot said. “The gentleman from Georgia has learned much since 1861; but he is still a laggard.”

“One Kentucky newspaper said this was the most impressive speech by a black man in American history. Now, that's saying something when you have Frederick Douglass out there giving brilliant speeches,” Foner said. “Elliott became a nationally known figure because of his speech on the Civil Rights Bill.”

With the votes of African American Congressmen Joseph Rainey, Richard Cain, James T. Rapier, and John Roy Lynch, that civil rights bill passed and on March 1, 1875 President Ulysses S. Grant signed it into law.

Author Lawrence Otis Graham said, "How gutsy was it for these guys not just to try to be elected, but to get seated and to actually demand equality."

Graham wrote a book about Mississippi Senator Blanche K. Bruce, who was born a slave in Virginia before becoming a successful plantation owner in Mississippi. Bruce and his wife Josephine were one of the wealthiest African American couples in America, and lived in a townhouse in an integrated Washington, D.C., neighborhood.

"This was not someone who was in over their head," said Graham. "This was someone who, despite all the odds against him, succeeded enormously."

Rocca said, "The year he's seated in the Senate, 1875, is the apex of black representation during Reconstruction; seven House Members and one Senator, that's the high point?"

"Yeah, it is. But he doesn't get to enjoy that high point very long with his colleagues," Graham said.

When neither candidate in the 1876 presidential election secured enough votes in the Electoral College to be declared winner, a deal was struck. Southern Democrats agreed to back Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes; in exchange, the federal troops who had protected black voters were withdrawn from the South. Just a few years later, the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Bill of 1875. Black voting rights were gradually stripped away, and black representation in Congress faded.

Reconstruction was over, and the Jim Crow era of segregation began.

For most of the twentieth century, Reconstruction was portrayed as a failure. D.W. Griffith's 1915 movies "The Birth of a Nation" depicted South Carolina's black state legislators as uncouth and given to drink, while also casting the Ku Klux Klan as heroes. The movie was a sensation with white audiences. President Woodrow Wilson even hosted a screening at the White House.

And most schools taught Reconstruction as a misadventure at best. Foner said, "That's what I was taught in high school in the 1950s: Reconstruction was the worst period in American history, it was a travesty of democracy, black people misused the right to vote, were not capable of serving in public office. That was taught everywhere."

For a young Henry Louis Gates, this was particularly painful. "The few black kids in my class would put the textbook up over our face and slink down in our chairs, because it was all so embarrassing," he said.

But over the last 25 years, Reconstruction in some schools has been given a much fuller treatment.

And in 2017, the Reconstruction Era National Monument was established in Robert Smalls' hometown of Beaufort, S.C. Just down the road, you can see the house he lived in as a free man and the church he attended. Alongside it is a bust of Smalls – the only known statue in the South of any of the pioneering black Congressmen of Reconstruction.

Episode Extras