Join our mailing list for the latest news on Mobituaries, plus receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

By clicking “Sign Up” I acknowledge that I have read and agreed to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Join our mailing list for the latest news on Mobituaries, plus receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

By clicking “Sign Up” I acknowledge that I have read and agreed to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

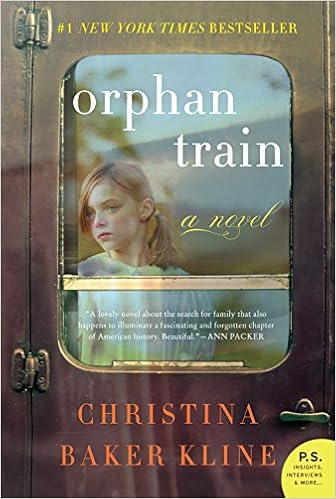

From 1854 to 1929, 250,000 abandoned or orphaned children in East Coast cities found themselves on journeys across the country. Shepherded by private organizations like the New York Foundling or the Children’s Aid Society, these orphans were resettled with families who promised to give them shelter, an education, and a place to grow up. It was an ambitious, unprecedented undertaking. It was the predecessor to our country’s modern foster care system. The experiment became known as The Orphan Train movement

New York in the 1850’s was a difficult place to live. There was an influx of immigration, high rates of infectious diseases, and poor working conditions led to children being abandoned at tragic rates. Some estimate the number of children on the street at the time ran as high as 30,000–in a city of only 600,000 people.

A missionary named Charles Loring Brace witnessed the struggles of these children firsthand, and decided that something had to be done. So, in 1853, he founded an organization called “The Children’s Aid Society,” and began forming a plan to send abandoned children from New York to communities outside the city that could take them in and give them homes.

In 1854, Brace sent 45 children from New York to the tiny town Dowagiac, Michigan. The journey required multiple trains and boats make the journey. Upon their arrival, all of the children found families and the Orphan Train movement was officially underway.

The Children’s Aid Society wasn’t the only organization that would take part in the movement. In an effort to counterbalance the protestant-leaning Children’s Aid, a Catholic organization, the New York Foundling Hospital,began to send their own trains out specifically to Catholic families. Other organizations followed suit. And by the time the last train left for Silver Springs, Texas, in 1929, a quarter of a million children had found homes.

Many of these children lived perfectly normal lives–some wouldn’t even find out they were adopted until they were much older. Others would have harder times–ending up in difficult or potentially dangerous family situations. So, 90 years later, it remains important to ask: were the orphan trains a good thing or a bad thing?

In this episode of Mobituaries, Mo Rocca shares rare interviews from the CBS News archives and tracks down a woman who is believed to be the last surviving Orphan Train rider.

Episode Extras